Pooling

An ode to a municipal natatorium.

It is hard to know if you are dreaming of the Moores Park pool, for it is as a dream.

An oval of blue water set in a pedestal a hundred years old, a fat old lady with Art Deco earrings. The dark green trees and shrubs all around and above, lush and unkempt. A set of bleachers to one side providing a place where people without reason can watch you swim. An inexplicable iron fence keeping them from joining you.

And lying on your back, floating with your face to the sky, you turn your head just enough to dunk your ear, and there it is: the equally magnificent Otto E. Eckert power plant, with its three horns, those smokestacks visible for miles.

It is the only municipal pool in which I long to swim, because it feels insane.

In open water, I want to swim far and juggle the waves. I want to do. But this small pool calms the urge to do through the implausible collision of these two 1920s monuments to public works – the sweet little natatorium, the gargantuan power plant.

The pool came first, its nomination to the National Register of Historic Places indicates. (The nomination, written in 1984, succeeded.)

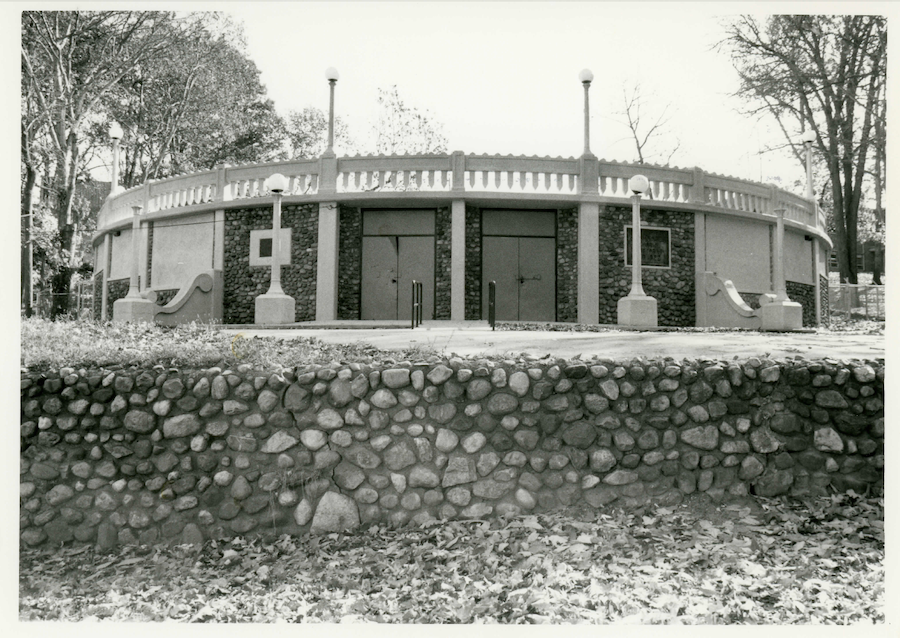

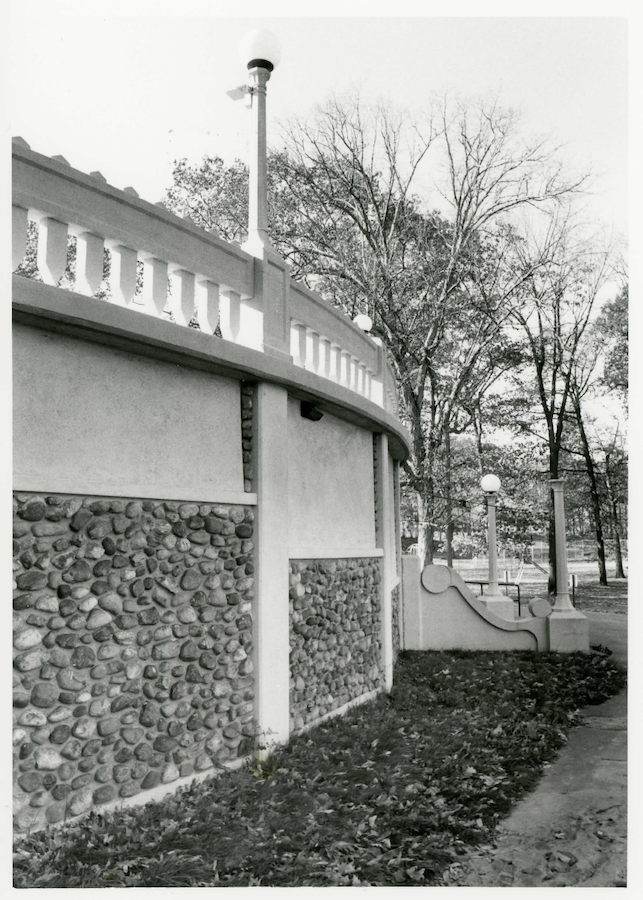

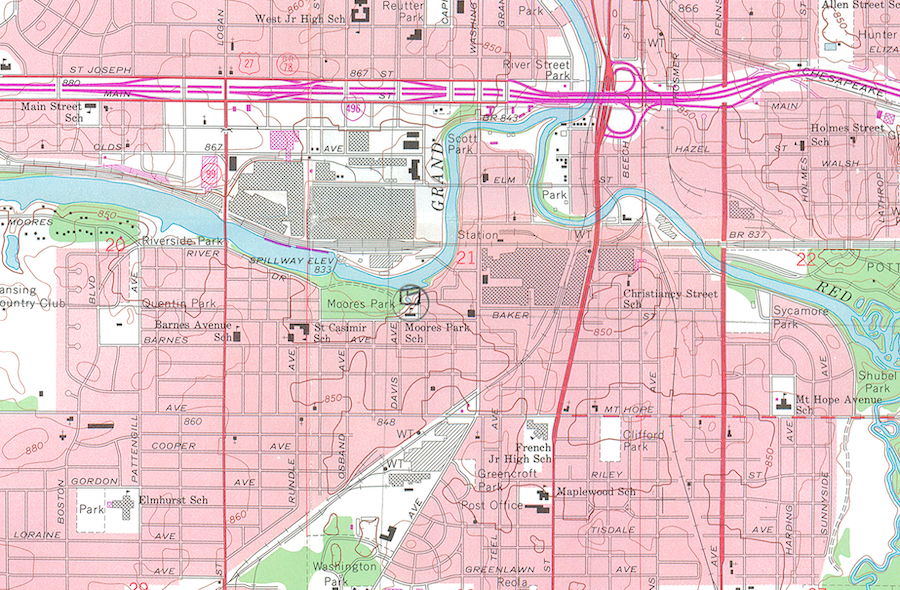

“The J. H. Moores Memorial Natatorium (commonly known as the Moores Park Pool) is located at the eastern edge of Moores Park in Lansing near the south bank of the Grand River,” the nomination says. “The pool is an ellipsoidal-plan, above-ground structure with pumphouse, showers, locker rooms, etc., located along the periphery of the pool wall. The pool is constructed of reinforced concrete and has a rubble-stone façade.”

Constructed in 1922, the natatorium is at once so humble and so grand it makes people who come upon it exclaim. Because it is built into a hillside, a first-time visitor to the park will often stumble upon it without realizing what it is until she is on the deck. From the ground in front of it, as you stand at the front doors, it looks like it might just be an overdecorated shed or maybe an old armory.

Charmingly, “A balustrade of reinforced concrete construction surrounds the upper deck. Fourteen concrete lamp standards with frosted glass globes…rise above the balustrade at regular intervals.”

It all looks ready for a synchronized swimming production number with flappers in their Hollywood bathing suits and caps. Does this explain the mysterious bleachers?

A man named J. Henry Moores donated the parkland in 1908 to the City of Lansing after making his fortune in real estate and “lumbering activities.” His investments included the Lansing Wheelbarrow Company, which, the nomination to the federal government instructs, “became one of the city’s largest firms in the late nineteenth century.” Who knew you could make a fortune in wheelbarrows?

When he gave over the land, Moores specified three conditions: that it always be a public park, that it always retain the name Moores Park, “and that no intoxicating beverages be used or sold on the property.” If I have broken that last rule, I have not been alone.

In 1922, fourteen years after Moores gave the land, a city engineer by the name of Wesley Bintz designed the pool. He must have been well pleased with his creation for, a year later, Bintz resigned his Lansing city job “in order to devote his career exclusively to swimming pool designs.”

“The Moores Park Pool is the prototype of what became known as the ‘Bintz Pool,’ an ovoid, entirely above ground structure containing locker and shower rooms and pumping and filtering equipment below the deck which surrounds the pool itself,” the historic-designation nomination explains. “The Bintz pool was especially suited to the needs of urbanized areas and could be designed to accommodate large numbers of users.”

It was only recently I learned this magic pool served as the model for hundreds of municipal pools – in Rutland, Vermont; Johnson City, New York; Rockford, Illinois; Montevideo, Minnesota; and beyond. Until it closed four years ago, having fallen into disrepair in a cash-strapped city, it was believed to be the oldest continuously-operated municipal pool in the nation.

The only mystery remaining is how it is the application for the historic designation made no mention of the pool’s behemoth brother, the Eckert plant, whose construction began in 1927.

The power-generation facility stands kitty-corner across the river from the natatorium so that you cannot possibly miss it as a swimmer; it is with you with every stroke. It mumbles a steady roar and burps and sometimes gives off a screaming test of its flood warning siren – a siren that will hopefully go off if the dam at the Eckert ever breaks. (Moores Park is a lowland, and the flood will drown everyone in it if they don’t run for the upper parking lot come time.)

I’ve swum at Bintz’s pool only a handful of times, for I have been faced with the challenge of getting in. It’s a Lansing Parks & Rec facility, and I’m an East Lansing resident. One time, I remember, I just snuck in while the staff was goofing off. One time, I convinced a Lansing friend to come over and get me in. Another time, I brought children in tow and had them smile and pout until we gained admission.

When the pool was shuttered, just before the pandemic, we devotees wept. A group sprung up to try to figure out what it would cost to fix it. Six million dollars, their volunteer experts concluded. It is no exaggeration to say I played the lottery for this pool.

And now, the pork cometh.

As everyone in the nation seems to know, the Democrats are finally in power in the Michigan legislature and in the governor’s office. There is much they still haven’t fixed. Most notably, they have yet to fix the state’s Freedom of Information law, which continues to be one of the worst in the nation, shielding state legislators and the governor from records disclosures. They have yet to institute anti-SLAPP legislation of the sort that would have helped me when a prison-bound real estate developer sued me for defamation despite having no case.

But they’re going to fix our pool, or at least send $6.2 million dollars trying. In the last week, an invitation went out to the community to come tidy up the place in preparation for the renovations. It brought a crowd much bigger than necessary. Had I known of the event in advance, I would have snuck in.

The metaphor presents itself – the pooling of public dollars and labor to bring us an oneiric restoration at a time when everything (Everything) is starting to feel surreal.

By next summer, if all goes well, the taps will be pushed open to fill the ovoid basin again. And when I find myself perceiving that I am in that water, floating and gazing at the stacks I look for on my way back home, I will again not know if I am just dreaming.