Artless

To listen, to digest, to create.

The other night, I read aloud to my mother and myself the final chapter of Anne Lamott’s Bird by Bird: Some Instructions on Writing and Life, and we ended up in conversation about my father. He died three summers ago, although for reasons I’ll explain in a bit, I grieved some forty years ago.

Lamott’s last chapter reads like all the hasty commandments your mother dumps on you just as you’re boarding a bus to go to a land where communication systems are known to be spotty. Lamott is trying to make sure her writing workshop ducklings – in this case, her readers – have all the last bits of her wisdom before they fall out of touch. And the chief thing she wants them to know is that writers gotta write: that they must write every day, no matter if a word is never published.

Her logic is not only that you have to treat your writing as you would a violin if you were hoping to be employed by a real symphony. (Pros keep practicing.) She also wants writers to understand that writing is how they process the world: it is how they listen, how they digest, and how they create. The practice of writing consequently makes you a better listener, keeps you from going hungry, and makes you useful.

My mother and I are both writers, which is the main reason I chose this book (with her consent) for us to take in together. But in the conversation we had afterwards, we talked about non-writers. And we concluded that all the people we know who are not writers have an art that does for them what writing does for us: helps them “hear,” helps them feel full, makes them feel useful.

My sister practices elegant medicine and writes poetry and music. My son builds things, including a pipe organ from scratch. My mother’s father conducted his artistry through the provision of soul food and childcare. (He was one of those rare people who could make any child behave by being kind.) Everyone has an art.

Everyone except Dad, that is.

We tried for a while, on the phone together, to think about what Dad’s art might have been. In his youth, he practiced a very pinched style of drawing, whereby he would execute exact replicas of various images – cartoon cels from Walt Disney, comic book superheroes, military airplanes in textbooks from his high school aeronautics class. But none of these were original, so far as we could recall. And we couldn’t think of any other art of his.

My father's name was Frank. And do you know what? Merriam-Webster names it as a synonym for artless.

Lamott says we must write because writing causes us to listen; art makes us absorb. But, in fact, my father did not listen. He always functioned as if there was nothing you could tell him that he didn’t already know. He did not digest what was happening around him. He simply ran what you said through his Morality Machine and told you the nature of your sin. And he most certainly did not create. He didn’t build anything, he didn’t paint anything, he didn’t draw anything. He never cared for poetry. (My mother writes poetry.)

This reflection on Dad’s artlessness finally led Mom and I to wonder to each other whether it might be the case that the saddest, most selfish, most difficult people on earth might be fundamentally lacking art. And the more I thought about this the next day, the more I realized that the very few people I have known in my life who appeared congenitally sad and always painful (like my mother's mother) indeed seemed to have no art. Some had professions. They had marriages and children. They had retirement accounts. But they had no art.

My father was what they termed then (and maybe still call) “a high-functioning alcoholic.” In middle school, for a nutrition class, my sister calculated how much of his calories came from beer: seventy-five percent.

Because my mother’s mother was also a drinker (at least one expensive bottle of cognac per day), because my mother’s brother died of drink (and who knows what he saw in the war as a child), my mother could recognize the alcoholism in my father even though he insisted she made up that diagnosis just to be mean.

She had the good sense to make her way to Al-Anon, the support group for families of alcoholics. And though I did not go – kids in those days were not invited to such adult things, no matter how adult our alcoholic parents forced us to be – I benefitted from my mother’s attendance as she brought the lessons home. Chief among them was this: You cannot fix someone who is broken, and trying will only break you. If they can be fixed, they have to do it themselves. But most of them can’t be.

My mother’s trickle-down Al-Anon prepared me for what the therapist I eventually retained would tell me when I was about twenty years old: that I was never going to have a real father, and that my life would be easier if I accepted that fact now and grieved the loss of a father rather than waiting until he died.

I had gone to this therapist, an Eastern philosophy-obsessed Presbyterian minister named George, in part to recover from having lost my virginity to a jerk of a teacher who used me for sex. George assumed, not unreasonably, that I got into that situation because I lacked a father and was hoping to find one. He wanted to break me of the idea of reliable fathers, I suppose. Some people had them, but the reality was I was never going to; men who slept with you because you needed a father were, by definition, terrible fathers.

And so George encouraged me to formally grieve. Really acknowledge to myself that he was gone. Go through the five stages, burn some candles, wear black for a few days, whatever.

As it turned out, formally grieving didn’t take that long. Working off of George’s advice, I quickly came to realize what I already knew: my father’s parents and childhood had permanently misaligned his spirit; he wasn’t my problem; I couldn’t solve him; and I didn’t need anything from him. The IRS understood me to be no one’s dependent starting at the age of 19. By that time, I had quit school and was supporting myself as a mortgage broker. I had my own car, my own apartment, my own bank accounts, my own books, my own art.

Deciding I had no father made it so much easier to deal with my Dad. Thereafter, I simply treated him like he was any of various people who had found their way into my life and with whom I had to politely deal. He was the neighbor who grouched about my car being parked where he wanted to park. He was the old lady in the produce aisle who told me I was crazy to pay for organic. He was the guy on the corner who shook a sign and warned of damnation.

By the time my father died, so many decades later than would have made sense for him and us, what I now realize was his artlessness had made me come to appreciate what I now realize was my mother’s artfulness. Despite being married to all his misery, she managed to cause us to listen, to digest, to create.

I don’t remember very much of my childhood, but I remember very keenly that one day it had rained so much and we were stuck inside bored, and Mama sat us down with heavy construction paper and crayons and scissors and told us to make big, colorful paper fish. While we did that, she took popsicle sticks and glued strings of yarn onto them, tying to the other ends of the yarn metal paperclips she bent into the shape of fish hooks.

After we had done our drawings, she poked holes into our fishes’ mouths, sat us on the edge of the bed, handed us the popsicle stick fishing poles, and told us to try to catch the fish. It was not the fishing that ended my boredom. It was the fascination with my mother, realizing for the first time that she had it in her to turn a bed into a dock.

There are not many photos of my mother as a young woman. My father, in spite, threw them all out about twenty years ago, when my son was young.

“He was jealous even of my life before him,” she said to me when she told me of this action. She told me about this about a month or so after he died. I thought I had stopped hating him forty years earlier, but I will admit, that day, I hated him as kin, fresh and anew.

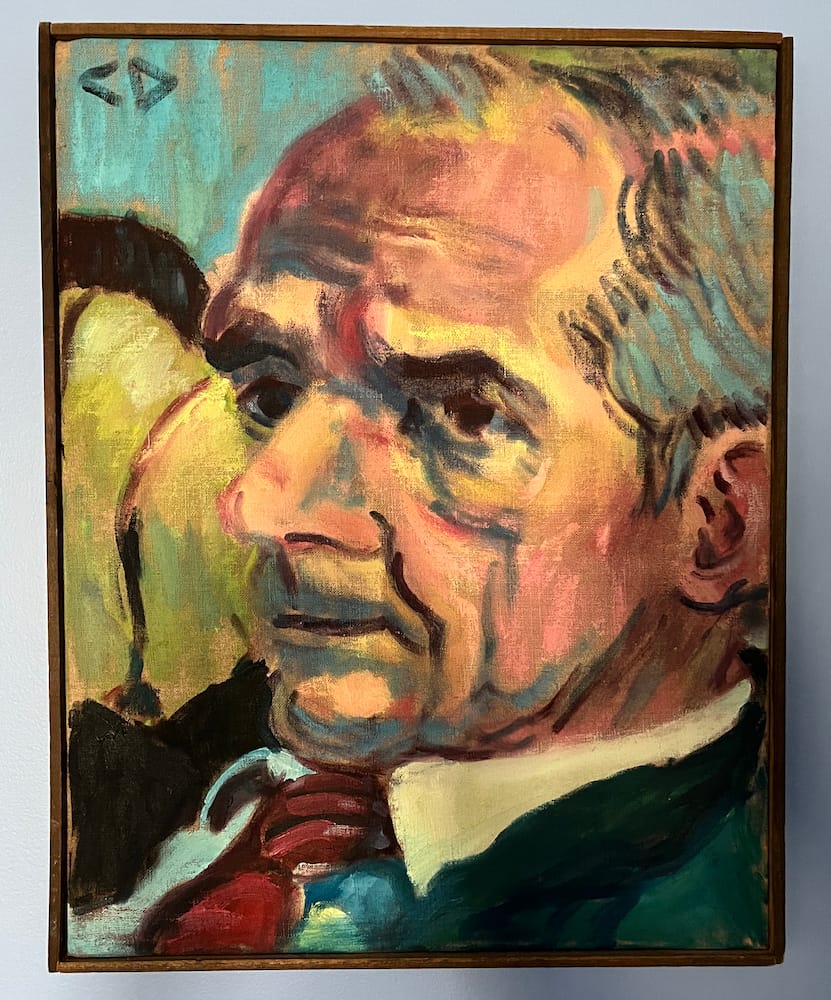

After reading Lamott, the other day I pulled up a picture I have on my phone, a rare photo of my mother as a young woman. She was in Germany, I think, a decade or more after the war, at about the age of twenty-four. She was painting there and elsewhere in Europe, I know, and writing. She told me once she had taken up work in a factory and as a hat-check girl at a nightclub in order to pay the rent, and that I should not tell her parents she had done these things, because she had never told them.

After finding that photo of my mother, I searched for and found, too, a photo of myself at about the same age. It is a picture of me reclining on an Adirondack chair at the outdoor Grantchester Tearoom just outside Cambridge, catching what there was of the English sun.

I sent my mother this pair of photos.

“Look at that,” I said. “You and I had exactly the same pixie cut at about the same age. Isn’t that funny, that we both had the same haircut thirty-something years apart?”

She looked at it a while and answered only, “My hair had blonde streaks then.”